1. Lithosphere

The Lithosphere or the earth’s crust (figure 2.0) is the outermost solid surface of the planet and is chemically and mechanically different from underlying mantle.

It has been generated largely by igneous processes in which magma (molten rock) cools and solidifies to form solid rock.

Beneath the lithosphere lies the mantle which is heated by the decay of radioactive elements. The mantle, although solid in nature, is in a state of rheic convection.

This convection process causes the lithospheric plates to move, albeit slowly. The resulting process is known as plate tectonics.

Volcanoes result primarily from the melting of sub-ducted crust material or of rising mantle at mid-ocean ridges and mantle plumes.

2. Hydrosphere

The hydrosphere is the water body of the Earth natural environment and has the following divisions,

Ocean– the ocean is a major body of saline water approximately 71% of the Earth’s surface is covered by ocean, a continuous body of water that is customarily divided into several principal oceans and smaller seas.

More than half of this area is over 3,000 meters deep. The average oceanic salinity is around 35 parts per thousand (ppt), and nearly all seawater has a salinity in the range of 30 to 38 ppt.

The major oceanic divisions are defined in part by the continents, these divisions according to descending order of size are the Pacific Ocean, the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, the Southern Ocean and the Arctic Ocean.

Rivers – A river is a usually freshwater natural watercourse, flowing toward an ocean, a lake, a sea or another river as seen in the figure above. In a few cases, a river simply flows into the ground or dries up completely before reaching another body of water.

Small rivers may also be termed by several other names, including stream, creek and brook. The water in a river is usually in a channel, made up of a stream bed between banks. In larger rivers there is also a wider floodplain shaped by flood-waters over-topping the channel.

Flood plains may be very wide in relation to the size of the river channel. Rivers are a part of the hydrological cycle. Water within a river is generally collected from precipitation through surface runoff, groundwater recharge, springs, and the release of water stored in glaciers and snow packs.

Stream – a stream is a flowing body of water with a current, confined within a bed and stream banks. Streams play an important corridor role in connecting fragmented habitats and thus in conserving biodiversity.

Types of streams include creeks, tributaries, which do not reach an ocean and connect with another stream or river, brooks, which are typically small streams and sometimes sourced from a spring or seep and tidal inlets.

Lakes – A lake is a body of water that is localized to the bottom of basin. A body of water is considered a lake when it is inland, is not part of an ocean, is larger and deeper than a pond, and is fed by a river.

Natural lakes on Earth are generally found in mountainous areas, rift zones, and areas with ongoing or recent glaciation. Other lakes are found in endorheic basins or along the courses of mature rivers.

Read Also : Earth as the Natural Environment

All lakes are temporary over geologic time scales, as they will slowly fill in with sediments or spill out of the basin containing them.

Pond – A pond is a body of standing water, either natural or man-made, that is usually smaller than a lake.

A wide variety of man-made bodies of water are classified as ponds, including water gardens designed for aesthetic ornamentation, fish ponds designed for commercial fish breeding, and solar ponds designed to store thermal energy.

Ponds and lakes are distinguished from streams via current speed. While currents in streams are easily observed, ponds and lakes possess thermally driven micro-currents and moderate wind driven currents.

These features distinguish a pond from many other aquatic terrain features, such as stream pools and tide pools.

3. Atmosphere

The atmosphere is the thin layer of gases that envelops the Earth and held in place by the planet’s gravity. Dry air consists of 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, 1% argon and other inert gases, such as carbon dioxide.

The remaining gases as seen in figure 2.3 are often referred to as trace gases, among which are the greenhouse gases such as water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone.

Filtered air includes trace amounts of many other chemical compounds. Air also contains a variable amount of water vapor and suspensions of water droplets and ice crystals seen as clouds.

Many natural substances may be present in tiny amounts in an unfiltered air sample, including dust, pollen and spores, sea spray, volcanic ash, and meteoroids.

Various industrial pollutants also may be present, such as chlorine may be elementary or in compounds, fluorine compounds, elemental mercury, and sulphur compounds such as sulphur dioxide [SO2].

Figure: Atmospheric gases scatter blue light more than other wavelengths.

Lightening is an atmospheric discharge of electricity accompanied by thunder, which typically occurs during thunderstorms, and sometimes during volcanic eruptions or dust storms.

4. Atmospheric Layers

The earth’s atmosphere can be divided into five main or principal layers and five minor layers. The five main layers are mainly determined by whether temperature increases or decreases with altitude while the minor layers are determined by other properties.

Principal layers include;

Exosphere– is the outermost layer of Earth’s atmosphere that extends from the exobase upward, mainly composed of hydrogen and helium.

Thermosphere– the top of the thermosphere is the bottom of the exosphere, called the exobase. Its height varies with solar activity and ranges from about 350–800 km. The International Space Station orbits in this layer, between 320 and 380 km.

Mesosphere – the mesosphere extends from the stratopause to 80–85 km. It is the layer where most meteors burn up upon entering the atmosphere.

Stratosphere– the stratosphere extends from the tropopause to about 51 km. The stratopause, which is the boundary between the stratosphere and mesosphere, typically is at 50 to 55 km.

Troposphere– the troposphere begins at the surface and extends to between 7 km at the poles and 17 km at the equator, with some variation due to weather.

The troposphere is mostly heated by transfer of energy from the surface, so on average the lowest part of the troposphere is warmest and temperature decreases with altitude. The tropopause is the boundary between the troposphere and stratosphere.

Other minority layers are;

The ozone layer – This is contained within the stratosphere. It is mainly located in the lower portion of the stratosphere from about 15–35 km, though the thickness varies seasonally and geographically.

About 90% of the ozone in the atmosphere is contained in the stratosphere. The ozone layer of the Earth’s atmosphere plays an important role in depleting the amount of ultraviolet (UV) radiation that reaches the surface.

As DNA is readily damaged by UV light, this serves to protect life at the surface. This layer also retains heat during the night, thereby reducing the daily temperature extremes.

The ionosphere – The ionosphere is the part of the atmosphere that is ionized by solar radiation, stretches from 50 to 1,000 km and typically overlaps both the exosphere and the thermosphere. It forms the inner edge of the magnetosphere.

Thehomosphere– The homosphere includes the troposphere, stratosphere, and mesosphere.

Heterosphere– The heterosphere is the upper part that is composed almost completely of hydrogen, the lightest element.

The planetary boundary layer – is the part of the troposphere that is nearest the Earth’s surface and is directly affected by it, mainly through turbulent diffusion.

5. Climate

The climate encompasses the statistics of temperature, humidity, atmospheric pressure, wind, rainfall, atmospheric particle count and numerous other meteorological elements in a given region over long periods of time.

The climate of a location is affected by its latitude, terrain, altitude, ice or snow cover, as well as nearby water bodies and their currents.

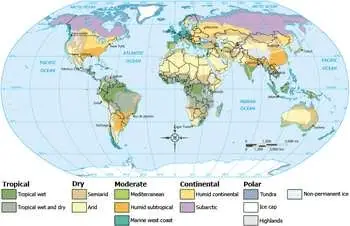

Climates can be classified according to the average and typical ranges of different variables, most commonly is temperature and precipitation. The most commonly used classification scheme is the one originally developed by Wladimir Köppen.

The Thornthwaite system, in use since 1948, incorporates evapotranspiration in addition to temperature and precipitation information and is used in studying animal species diversity and potential impacts of climate changes.

6. Wilderness and wildlife

Wilderness is generally defined as a natural environment on earth that has not been significantly modified by human activity. Wilderness can be defined in more detail as the most intact, undisturbed wild natural area left on our planet – those truly wild places that humans do not control and have not developed with roads, pipelines or other industrial infrastructure.

Wilderness areas and protected parks are considered important for the survival of certain species, ecological studies, conservation, solitude, and recreation. Wilderness is deeply valued for cultural, spiritual, moral and aesthetic reasons. Some nature writers believe wilderness areas are vital for the human spirit and creativity.

Figure: a typical example of a mountainous wilderness

Wildlife includes all non-domestic plants, animals and other organisms. Domestic wild plant and animal species for human benefit have occurred in many places all over the planet, and have major impacts on the environment, both positive and negative.

Read Also : Methods of Disposal of Waste Pesticide Containers

Wildlife can be found in all ecosystems. Deserts, rain forests, plains, and other areas including the most developed urban sites all have distinct forms of wildlife.

While the term in popular culture usually refers to animals that are untouched by human factors, most scientists agree that wildlife around the world are impacted upon by human activities.